skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Markéta Luskačová: A Photographic Pilgrimage

One of the Czech words for photography is “zvecnit,” which literally means “to immortalize.” Although old fashioned and colloquial, it’s somehow appropriate when discussing the photographs of Prague native Markéta Luskačová. Since taking her first pictures in 1963—inspired by a chance meeting with pilgrims traveling to the medieval city of Levoča—she has devoted herself body and soul to documenting cultures and traditions under threat of being consigned to history. Another, less welcome influence on her photography was the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague, a brutal expression of state power that enhanced her empathy for those living outside the boundaries of government approval. For the next several years she concentrated almost exclusively on photographing religious pilgrimages. While not exactly banned under communist rule, they were characterized by a kind of semi-legal status, in which participants were directly and indirectly persecuted by the state. When Luskačová emigrated to London in the mid-’70s, however, she expanded her focus to include religious pilgrims in Ireland, the homeless, children from various walks of life and, most evocatively, London’s Brick Lane Market, a Dickensian enclave teeming with gritty atmosphere and hardscrabble realities. Yet Luskačová strives to highlight basic human values like compassion, tolerance, integrity and solidarity. Such values may seem out of place in our impersonal technological world, yet her work suggests that they hold the greatest (perhaps only) potential for personal salvation.

Markéta Luskačová

Markéta Luskačová

I first came across your work in the August 1969 issue of Camera magazine, in which the writer Anna Farova, described you as an autodidact. She also wrote: “Marketa Luskacova is not in the least concerned about the traditional rules of photography and she unashamedly neglects the technical side in her pictures.” Looking at your images, however, it seems that you are very much in control of photographic technique. Do you know what Farova meant?

I met Anna Farova for the first time in 1965, when I was a student of sociology. I was writing my end-of-year essay on the link between sociology and photography. She had an extensive library and kindly lent me books on the Farm Security Administration, Dorothea Lange, Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis. On that occasion, I showed her my photographs, and she understood that I could expose the film, develop it and print pictures, so she could consider me an autodidact. But in 1969, when she wrote the piece for the Camera, I had already graduated in sociology of culture at Prague’s Charles University, and I was a second-year student in a postgraduate photography course at Prague FAMU. I am not sure that she knew that. She also wrote that I was a student of political science, which I certainly was not. But I remember that she wrote quite nice things about my photographs.

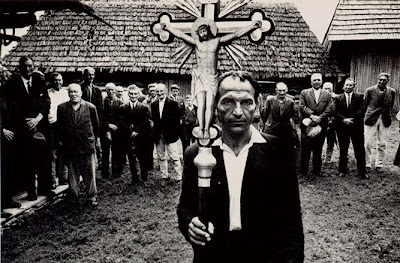

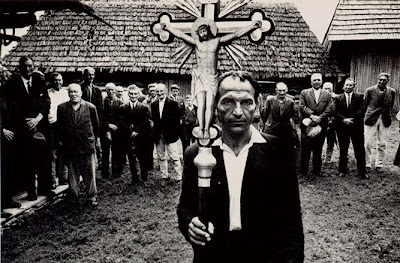

Men with a cross, Kalvaria Zebrydowska, 1968

Men with a cross, Kalvaria Zebrydowska, 1968

Can you talk a little about your beginnings as a photographer?

During my first year at Charles University I took part in a field exercise, the aim of which was to assess the cultural awareness of the residents in a small village near Prague. Each student had a questionnaire to fill out with 10 different people. One villager I questioned was a young girl, a factory worker. I was showed her five postcards as part of the survey: a still life, a 19th century portrait, a landscape, a kitsch birthday card and a modern painting. I then asked her which she liked, disliked, objected to, etc. She looked at the postcards for a very long time, then she laughed and she said she liked them all very much. And she had such a beautiful smile and such an amused expression that I wished I could photograph her—I felt that the photograph would be far more valuable than any statistics I could come up with. I wanted to be a photographer. Later that year I was hitchhiking in Slovakia and I met pilgrims going to the medieval pilgrimage city of Levoca. Then and there I made the decision to become a photographer and to photograph these pilgrims. In communist Czechoslovakia the pilgrimage was something very rare and contrary to state ideology. I wanted to record the pilgrims’ way of life, because I thought that it would not survive for much longer.

Funeral of Janko Adam, shepherd, Sumiac, 1971

Funeral of Janko Adam, shepherd, Sumiac, 1971

Did your childhood and/or the political and cultural environment of Prague have an impact on your photographic concerns?

When communism began in Czechoslovakia there was a big upheaval in my family, during which my grandfather broke both of his hips. He and my grandmother became homeless and went to live with my parents. My grandfather became a housebound invalid. As a young man he was an artist, and art remained his lifelong love. I was his only companion, and he very generously shared this love with me. What was a sad ending of his life for him was a very good beginning of life for me.

You photographed the Soviet invasion of Prague in 1968. What effect did the invasion have on you personally?

My photographs of the Soviet invasion in 1968 are a very personal testimony, an expression of bewilderment, despair and unspeakable sadness. When I decided to go live in the West, I left my best negatives with a friend in Prague, because if the negatives were to be found in my luggage at the airport, I would not have been able to leave the country. I also left with this friend my negatives of the Soviet invasion. Unfortunately, his home was raided by the secret police, who were looking for anti-government documents. They did not find my negatives. However, after the police left, my friend, out of fear that they might return, burned my best negatives of the invasion.

Mr. Ferenc singing, Obisovce, 1967

Mr. Ferenc singing, Obisovce, 1967

Have you ever shown those pictures?

For years I searched in vain, trying to find at least some prints. Only recently did I find some photographs from the 1968 invasion in a box of my letters to my father, which his second wife gave to me after he died. He lived in the country, and I had sent him some photographs so that he could see how it looked in Prague in those days. I had totally forgotten that I sent them. About 20 of them were exhibited for the first time in the spring of 2009 at Michigan State University. Four photographs were exhibited and published in a catalog of a large show mounted to mark the 40th anniversary of the Soviet invasion in Prague.

Czech photography has a rich history of innovation. Do you feel kinship with other documentary photographers like Josef Koudelka or Milon Novotný? And did you associate with any Czech photographers?

I used to visit an old and famous Czech photographer named Josef Sudek. He described my questions about his photographs as “picking his cherries.” Josef Koudelka is an old friend. We became friends in 1963, when he was working in a Prague airport designing aircraft. Milon Novotný was a friend of my husband, and once a week we would go to the pub together.

On death and horses and other people, 1998

On death and horses and other people, 1998

Is there such a thing as a “Czech” photographic aesthetic?

I don’t think so. But Czechs and Slovaks take photography very seriously. The Czech avant-garde art groups in the early 20th century included writers, painters, photographers and sculptors. And even during communism the official state body “The Artists Union” had departments of painting, sculpture, printmaking and photography. I became a member of The Artists Union in 1969, and in my identity card, in the column “profession,” was written: “visual artists—photographer.”

What year did you leave the Czech Republic, and why did you settle in London?

I left very late; I think it was seven years after the Soviet invasion. My reasons for settling in London were several. Let’s name one: I love London.

How do you typically choose your projects?

There is no typical way in which I choose my themes. Sometimes it almost feels as if the theme chooses me, sometimes irresistibly so. Sometimes one theme leads to another, or evolves. For example, when photographing the pilgrims in Slovakia, I noticed another, very distinctive group of pilgrims coming from the mountain village of Sumiac. When I went to visit them, somehow the theme of the traditional mountain village took over, and for the next seven years I photographed that village.

Two women with a cigarette, Chesire Street, 1977

Two women with a cigarette, Chesire Street, 1977

You seem drawn to marginalized groups of people.

I am quite often photographing people with a way of life that I think might not last for much longer. I want them and their way of life to be recorded. Photography is a great tool for remembering.

Do you spend a lot of time with your subjects before photographing them?

I spend a lot of time with people while I am photographing them. This is because I almost always take a very long time. By the time I finish photographing them, they are my friends. Take the picture “People around a Fire, Spitalfields.” I regularly stopped there for a month, and only took pictures when those men invited me to.

People around a fire, Spitalfieds, 1976

People around a fire, Spitalfieds, 1976

I’m struck by the graphic power of your work, especially the strong contrast and pronounced grain. How did you arrive at this visual aesthetic?

In Czechoslovakia in the 1960s high-speed 35mm photographic film was not available. We used high-speed cinematographic film, which we bought on the black market from film cameramen. When pushed, the film was quite grainy, and I liked it very much. The style was born out of necessity, but I like the grain, I like the texture, even the faults in the emulsion. I don’t mind them; I consider them part of the image.

Do you enjoy working in the darkroom?

I consider photography pure magic, and I enjoy working in the darkroom very much. Unfortunately, in the past few years I get sick when printing for a long time and inhaling the chemicals. So I do work prints and the first print, which is used as a guide. My modern prints are usually made by a professional printer. My early vintage prints were all made by me. Once in Prague, when I was printing, I heard my neighbor’s little girl crying outside. Her mother was not at home, so I invited her to wait in my darkroom. She was watching me dodge the prints under the enlarger and then put them in the developer, when suddenly she said: “Markéta, you are a witch.” And I said, “Of course, didn’t you know?”

Man singing in Brick Lane, 1982

Man singing in Brick Lane, 1982

There’s an artlessness, or perhaps an innocence, to the way you frame your images that almost seems to transcend the notion of composition. Do you find yourself in a particular mood or mindset when you press the shutter?

I often stay in one place for a long time, or I walk for hours on end. Hours, days, even years. You cannot take a picture unless you are there with the camera. It is very lovely to find myself in a particularly exalted mood when pressing the shutter, but this is the reward, not a vantage point. From Josef Sudek and Josef Koudelka I learned how long it takes to get a good photograph.

Do you find that the apparent visual simplicity of the images better serves to amplify their emotional complexity?

I like the simplicity of the images; that way I can say things more clearly. But not all my pictures are simple.

You have a way of confronting your subjects directly, but making it feel like a collaboration rather than a challenge. They don’t flaunt their emotions, but they don’t hide them, either. Moreover, the almost stylized intensity of their expressions and gestures sometimes makes it seem as if they are performing for you, even if they’re unaware of doing so.

The art of posing the photograph is different from that of taking things as they are. I think my best pictures are not a result of a “decisive moment,” they are done in a “moment of trust.” No picture of mine was staged or posed by myself. Sometimes people spontaneously posed for me and I simply took the picture, which they offered.

Sclater Street, London, 1975

Sclater Street, London, 1975

You often group subjects in threes. Do you attach any significance to this number?

Good spotting! I never thought of it. Three is a beautiful number.

Your work is rooted in documentary tradition, yet the emotion and visual drama take it into another realm beyond documentary. How would you describe your photography?

I never liked the label documentary photographer. In a visual arts context the expressionist style is the one I feel closest to. But I consider myself simply a photographer.

There is something strange and familiar, comforting and disturbing about your photographs. Are you aware of this dynamic?

Yes. I like the tension, the ambiguity, the mystery in the pictures.

Your work has a visual poetry that seems perpetually balanced between light and dark.

Since childhood I have been an ardent reader of poetry. In London, in order to keep my Czech language, I would read Czech poetry every night before dropping off to sleep. If you sense it in my pictures, it comes from inside. Yes, I very much try to achieve a certain balance.

Edward with clock, off Cheshire Street, 1978

Edward with clock, off Cheshire Street, 1978

Even the objects in your photographs are weighted with character and significance, like the clock in the image “Edward with clock, off Chesire Street.” There’s an ambiguous yet tangible relationship between man and machine. He seems to be holding it up for inspection to an unseen customer, yet the gesture can also be read as if he were acknowledging the passing of time, or contemplating his irrecoverable youth. Is this an intended effect or the result of serendipity?

Sometimes it is intended, and sometimes it is a lucky accident, spotted only in the darkroom.

So much of your work has focused on religious rites, and how they emphasize a recognition and acceptance of mortality. Why are you drawn to religious imagery? Are you a religious person?

Yes, it appears that I am drawn to religious imagery. But my early Slovakian photographs should be viewed within the frame of time and place in which they were taken. In communist Czechoslovakia the expression of faith of any kind was against official Marxist ideology and was oppressed. In my childhood the communists raided the monasteries at night, arresting nuns, monks and priests. They spent their prison sentences working in uranium mines, which destroyed their health. People who practiced religion were called “reactionary elements.” They were often able to work only as unskilled laborers, even if they were university-educated. Their children were often denied education, being labeled “undesirable backwards elements.” My photographs are not only of people practicing religion, they are a testimony to human integrity.

Funeral, Sumiac, 1970

Funeral, Sumiac, 1970

One month after the democratic revolution in December 1989, the director of the Levoca Museum called me in London and offered me a show in the summer of 1990. He had been aware of my photographs of pilgrims from 20 years previously, but told me that his museum would have been closed had he exhibited them. When I went to the opening, the curators recalled how they used to attend such pilgrimages late at night, wrapped in black scarves for fear of being discovered. Had they been recognized by the communist secret police, they would have lost their jobs.

You also focus on people living outside of the mainstream—mountain villagers, homeless people, battered women, disabled children, street musicians and peddlers. What kind of universal qualities do you try and capture in these diverse subjects?

I just try to photograph people as individuals, rather than universal qualities and subcultures. Sociology is gone from the radar.

Close to Prague, 2009

Close to Prague, 2009

Have your thematic intentions changed at all over the years?

I think the mood of my pictures is changing. I would like my photographs to be more upbeat. I am not sure that I am succeeding.

What projects are you currently working on?

I take a terribly long time with my photographs. I still photograph in Brick Lane when I am in London. I have not found in London any other better place to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. In Prague I still photograph carnivals. The photographs are part fairy tale, part horror story. I have photographed them for over a decade. The carnivals were banned during communism, because they were considered part of the Catholic calendar. There was a certain Renaissance when democracy returned to the country—many of the old customs were resurrected. At the moment I am calling this series “On Death and Horses and Other People.” I think it will be good.

The widow Ila Krivanova, sumiac, 1972

The widow Ila Krivanova, sumiac, 1972

[I wrote about Luskačová’s work in issue #73 of Black and White magazine. Check out more of this extraordinary photographer’s work at: www.marketaluskacova.com.]

Myron H. Davis: The Last Photographs of Carole Lombard

When Carole Lombard took the stage of the Cadle Tabernacle during a war bond rally in Indianapolis, Indiana on the evening of January 15, 1942, no one present could have foreseen that it would be her last public appearance. The Academy Award-winning actress, famous for such classic comedies as My Man Godfrey (1936), had embarked upon a three-day fund-raising tour at the urging of her husband, Clark Gable, following the United States’ entry into the war in December 1941. Lombard helped raise more than $2 million in support of the war effort as she charmed crowds in her home state with her beguiling blend of Hollywood glamour and unassuming nature. Prior to leaving the 10,000-seat auditorium she addressed the crowd one more time: “Before I say goodbye to you all, come on and join me in a big cheer! V for Victory!” At 4 AM the next morning, Lombard boarded Transcontinental and Western Airlines Flight #3, accompanied by her mother, Elizabeth Peters, and MGM publicist Otto Winkler. Approximately 23 minutes after refueling in Las Vegas, the plane slammed into Table Rock Mountain (located 32 miles southwest of Vegas) a couple hundred feet below the peak, killing all 22 people aboard. Lombard was only 33 years old. Of all those who attended that final rally, perhaps none has a more vivid recollection of the actress’ last hours than the man who took her last photographs. Myron Davis was then working as a stringer for Life magazine, and he would soon become the magazine’s youngest accredited war photographer, covering several amphibious landings in the Southwest Pacific. Davis documented Lombard’s official activities during her tour, and his picture of Lombard leading the crowd in singing the national anthem appeared in the January 26, 1942 issue of Life under the headline: “Carole Lombard Dies in Crash After Aiding U.S. Defense Bond Campaign.” Myron H. Davis working on a troop train story for Life during World War II.

Myron H. Davis working on a troop train story for Life during World War II.

Can you talk about the context in which these images were made?

Well, you have to remember that there was a huge amount of patriotism at that time. People were shocked about Pearl Harbor and believed that we were an innocent country that had been viciously attacked. Lombard was very patriotic herself, and was, I believe, the first big Hollywood star to sell raise money for the war effort. Later, of course, Bob Hope and Bing Crosby were noted for traveling to overseas bases and putting on big stage shows for the soldiers. But this was the first war bond rally in the country, and I think Lombard’s death inspired other Hollywood stars to follow her example.

Take me through some of her activities on this tour.

Lombard didn’t like flying, and had taken a train from Los Angeles that was bound for Chicaco. The train made a brief stop in Salt Lake City on January 13, where she spoke to people waiting on the platform and sold some war bonds. Then she got back on the train and proceeded to Chicago, where she sold more bonds and did some interviews. From Chicago she flew to Indianapolis on Wednesday evening, and met her mother at the train station the next morning.

Her first official appearance that day was at the Indiana statehouse. Also attending were the governor [Henry F. Schricker], the publisher of The Indianapolis Star [Eugene C. Pulliam] and Will Hays, who was responsible for the notorious Hays Code of film censorship. The governor made a speech while Lombard stood on a stepstool and personally performed the flag-raising ceremony. She was wearing a fur coat, on account of the cold weather, but she was very down to earth. She didn’t have any “actress” airs about her. After the flag-raising, she signed the first shell fired by the United States in World War I, gave a short speech and then signed autographs for the crowd. I remember that she and the governor and Hays stood in a row at one point and gave the “V for victory” sign for a newsreel camera crew.  Lombard raises the flag as Indiana Governor Henry F. Schricker addresses the crowd.

Lombard raises the flag as Indiana Governor Henry F. Schricker addresses the crowd.

Then everybody went inside the statehouse building, where Lombard sold war bonds for about an hour or so. She was very good with the crowds, and very spontaneous. She handed out special receipts to everyone who bought a bond. These receipts had her picture and signature printed on them, plus a special message. I still have one, in fact. It read: “Thank you for joining me in this vital crusade to make America strong. My sincere good wishes go with this receipt which shows you have purchased from me a United States Defense Bond.”

She was then driven to the Claypool Hotel, where she was staying, for another flag-raising event. I think it might have been to commemorate the opening of an armed forces recruitment center. After that she went to the governor’s mansion for a big formal reception — busy day! And then that evening, she appeared at another war bond rally at the Cadle Tabernacle, where she gave a patriotic speech to get the crowd fired up. The last thing she did was to lead the crowd in singing “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Did you have much personal interaction with her during the tour?

I was with Lombard for three days, traveling all around. She put in a lot of long hours, and I tried to go wherever she went. We passed a few words here and there, but she knew enough about photography to just let me do my job, and I just let her do her thing and documented it.

Your most famous shot of Lombard is the one in which she’s singing the national anthem onstage.

I knew that the Cadle Tabernacle was the last place that she was to perform publicly before heading back to the West Coast. It was this huge auditorium that was standing room only and filled with patriotic signs put up everywhere. When I got up on the stage I saw way back on the far wall this big sign that read, “Sacrifice, Save and Serve.” That pretty much summed up the mood of the country right then, and I said to myself, “Wow. I’ve somehow got to get that sign as part of the image.” Lombard leads 12,000 patriots in singing the national anthem.

Lombard leads 12,000 patriots in singing the national anthem.

What equipment did you use for this image?

I used my Speed Graphic and Eastman Kodak Double XX film. I had a battery-powered Heiland flashgun on my camera fitted with a reflector and a #3 Wabash Superflash bulb, which was the most powerful one on the market back then. I framed the shot to illuminate both Lombard and part of the audience to her left. I also had a couple of stagehands point flashtubes with #3 flashbulbs at the front and middle rows to help light what was a really large crowd. Fortunately I got a pretty good negative, but when I had to make an 11x14 print for Life magazine, I had to dodge and hold back some of the sign in the background to make it legible.

I understand you had a close encounter with Lombard at the airport before she got onto her plane.

I was pretty doggone tired after taking that last picture of her, not realizing what a historical moment it was going to represent. I had to catch a plane at the Indianapolis airport at around three or four in the morning. I took a cab there and arrived early. I was practically the only passenger there. So I’m sitting on this wooden desk, half-asleep, when I sensed somebody come in and sit next to me. I felt a fur coat pressing against the side of my leg. Well, of course I knew it must be a woman, but I was so surprised when I opened my eyes and here was Carole Lombard sitting right next to me! We were so close together it was almost like we were boyfriend and girlfriend. I was so startled that it made her laugh, and then I laughed, too. I guess both of us were the kind of people who tried to see the sunny side of life.  Davis captures Lombard’s ability to connect with people from all walks of life.

Davis captures Lombard’s ability to connect with people from all walks of life.

I had sensed from the start of working with her that she was a wonderful, down-to-earth lady. Being in Hollywood and being a star and being married to Clark Gable hadn’t gone to her head.

So we just sat there and talked about a few of the day’s events. I thanked her for being so cooperative and letting me follow here around and do my thing. And she said, “Well, I was happy to do it, Myron.” I don’t think I called her by her first name. I probably called her Miss Lombard. Being the kind of lady she was, she said early on, “Just call me Carole.” It was a very sincere personal exchange between the two of us thanking each other for working on a job that we both thought was necessary for the country at that time.

Her mother and a Hollywood press agent were also there, standing in front of me. Neither of them spoke much. Carole and I were doing all the talking and laughing until they called her plane. We weren’t there together very long. I would say I talked to her for about five to ten minutes. Her plane was called shortly before mine, and then I got on my plane and fell asleep right away.

Did she talk about her fear of flying?

Yes. She told me she was really afraid of flying, but that she didn’t want to spend three days — and she used this expression — on a choo-choo train to go back to California. So this is another tragic part of it. It was almost like she had a premonition of some kind.  Ever the professional, Lombard held this V for Victory pose until Davis could make the shot.

Ever the professional, Lombard held this V for Victory pose until Davis could make the shot.

You didn’t take any photographs of her at the airport?

No, my equipment was checked in, except for my Leica, but I wasn’t going to bother her any more. I’d been following her around with my camera for three days and nights, and it was obvious that she and her mother were tired, like I was. I always tried not to impose on people.

So your Cadle Tabernacle pictures are the last ones that anyone took of her.

Yes, I’m convinced that’s true. I don’t remember seeing any other photographers at the auditorium. And I don’t think anybody else was at the hotel waiting to take her picture after the event wrapped up. I’m certain that the “Sacrifice, Save and Serve” picture Life ran was the last one taken of Carole Lombard while she was alive.

It must have been quite a shock to hear the news about her death.

I was married at the time and living on the south side of Chicago. We hadn’t been married all that long. I was still in bed trying to get some sleep from all this round-the-clock stuff, when my wife comes in, shakes me, wakes me up and says, “New York is on the phone. They want to talk with you.” It turned out to be Life magazine calling. They said, “Myron! You’re sleeping? Where are your Lombard pictures?” I said, “Well, they’re here with me. What about them?” “Oh, you don’t know? There was a plane crash and she was killed. We want those pictures here. Go downtown, develop the negatives and make four 8 x 10 prints. We’ve arranged for you to go to the Associated Press offices, and they will transmit the pictures to us. We’ll look at them and tell you which one we want. Then go back to the darkroom and make an 11 x 14 print, and then go down to the Donnelly printing plant—which was on 22nd Street just off the lake—and deliver this personally. And you’ve got to do that as fast as you can.” So that's what I did.  Lombard puts on the charm at the governor’s mansion prior to her final public appearance.

Lombard puts on the charm at the governor’s mansion prior to her final public appearance.

Once the editors in New York knew that the plane had crashed and that Carole Lombard, her mother and her agent had all been killed, they stopped production of the issue they were working on. At that time the editions for the entire country were printed here in Chicago at the R.R. Donnelly printing plant, and then shipped to the New York and the East Coast and the West Coast. They stopped production on that entire issue until I did what they wanted me to do. That may be the one and only time that Life stopped production on an issue.

As it happens, Life ran just the one image of Lombard. Did you try to do anything else with the pictures you took of her?

Some time after it had happened and after I had gotten over the shock of it, I went to the Life darkroom on the fifth floor of the Carbon and Carbide building on Michigan Boulevard. I spent hours making 11x14 prints that I had taken during her tour, maybe 25 or 30, boxed them up and sent them to Columbia Studios with a letter addressed to the top executives. The letter read: “This may not be the time to deliver these to Clark Gable. There may, in your opinion, never be a time to deliver these pictures to Clark Gable. But I’m leaving this up to your decision. If you think he might want to have these sometime, please deliver them to Mr. Clark Gable.” I never found out whatever happened to them. I never got a response, not from the studio, and certainly not from Gable. But I don’t believe these shots would have been tossed out.

[This interview was conducted in 2009 for a B&W magazine story. Myron H. Davis died on April 17, 2010 from injuries incurred during a fire at his apartment in Hyde Park, Chicago. He was 90 years old. Signed vintage and modern prints of Davis’ Lombard images can be ordered at: www.davidphillipscollection.com.]

Philip Ringler: Darkness Ascending

Philip Ringler likes to get at the deep dark center of things. His photographs, while rooted in tangible objects and settings, seem drawn from the depths of a starless subconscious. They might be images encountered in a nightmare, disorienting glimpses of subterranean memories, emotions and experiences. Intriguingly, the darker the visuals, the more truth is revealed. Ringler affirms that he photographs states of mind, but his work is less about himself than about such universal issues as alienation, abandonment, suffering and, perhaps most important, a kind of redemption. For Ringler, form and content are inextricably linked. His high-contrast black-and-white photographs are created in the darkroom on textured silver gelatin paper with a homemade developer; the prints are hung using rare earth neodymium magnets without frames or glass to encourage and assist viewers to pass through into the other side. The organic, labor-intensive nature of the process itself evokes the struggle to find meaning within ourselves, our activities, and our place in the world. Born in Walnut Creek, California, Ringler currently resides in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he maintains a photography studio, and further contributes to the medium as an instructor, lecturer and associate curator. He recently took time to discuss some of the thematic implications of his Nocturnal Sunrise series.  Philip Ringler

Philip Ringler

What made you want to become a photographer?

When I was young my family would go on road trips to different tourist attractions across America. I remember standing in front of numerous famous monuments in order to have the rigidly posed “here’s the proof that I was here” photograph taken. Although I understood the basic idea of “capturing the moment” and the sentimental quest to preserve memory, I didn’t feel that those kinds of images were particularly exciting to look at. So I made a decision during one of these vacations to take a plastic disc camera and photograph things I found interesting that had little to do with the specified “points of interest.” I made pictures of chipmunks, feathers submerged in puddles, rusted garbage cans, bent signs, tiny plants growing out of cracks in the sidewalk, etc. I found this new way of interacting with my environment to be really exciting. The act of looking through the viewfinder and composing the world gave me a feeling of creative and personal empowerment. It was like photography gave me permission to care about and examine things that most people considered to be irrelevant.

Refuge

Refuge

What specific aspects of the medium appeal to you?

I’m a fan of the photographic medium in all of its myriad permutations, but I am strongly interested in the philosophical aspects, especially the idea of questioning photography’s relationship to consensus reality. I approach photography from a non-documentary perspective, where the things and places in the images are not intended as representations of the outside world, but are like sets and characters from a film or play. The images may be derived from things that exist in the world, but they are transformed by the nature of the medium. Quite simply, photographs are not the things themselves. So questions like, “what is that” or “where is that” somehow become less important than the emotional and visceral responses that a viewer may experience. I attempt to further de-contextualize images by exploring scale, composition, tone and titles, all in an attempt to move the reading of an image away from the literal and closer to the poetic.

What kinds of things helped determine your creative direction?

I grew up in a relatively affluent suburban community where the dominant worldview seemed to be concentrated on the material and superficial, a version of life that I chose not to relate to. I always felt lost in this environment, but fortunately I found solace in things like photography, drawing, poetry and music. I wanted to live my life differently and find a more creative community. In college I became involved in the San Diego, and later the San Francisco, underground music scenes as a journalist, photographer and musician. There was a sense of freedom and unbridled creativity that I hadn’t experienced before. It was a necessary experience for me, but not a place I needed to live in forever. After entering graduate school I drew from my past experiences and found ways of translating them into more universal forms. Black Sun

Black Sun

The phrase Nocturnal Sunrise evokes a seeming contradiction, and signals the viewer to prepare for an unsettling or destabilizing visual experience. How did you come to choose that title?

The title Nocturnal Sunrise is a direct reference to the image of the Black Sun, the darkness that emanates its own source of light. It is an archetype that corresponds with a crucial and difficult stage of personal transformation where you may face unresolved issues, latent fears, trauma, sickness, depression and mourning. The idea is to examine this emotional terrain in order to accept and integrate it. It is about letting go of attachments to suffering and learning to navigate the darkness armed only with compassion and an open mind.

Where were these images taken, and what are your criteria for choosing locations?

I travel to various locations across the U.S. and beyond. I am drawn to certain types of places like amusement parks, decaying urban environments and similar areas where I’m likely to find evocative imagery. I wander around in a state of heightened awareness looking for interesting graphic and metaphorical elements to figuratively punch me in the stomach. I choose not to reveal the specific locations where I photograph, not because I am afraid that people will steal my ideas, but to emphasize the importance of the image itself. For me, these photographs are not tied to specific things or locations, but contain an opportunity for the viewer to create whatever narrative or meaning they want. The photographs themselves function as self-contained realities that are separated from the medium’s assumed ties to documentation. Chrysalis

Chrysalis

You seem to favor urban wastelands and dilapidated interiors — a comment on modern civilization, perhaps?

“Dilapidated interiors” is an interesting phrase because of its implied double meaning in my work. Interiors in my photographs are visual equivalents for the mind and spirit, the inner landscape of the human condition. The dilapidated qualities of these interiors suggest a possible commentary on the nature of the mind in relation to modern civilization. We live in a fast-paced age of information overload, and without slowing down every now and then our minds may resemble these entropic states of disarray. The images can serve as tools for contemplation and deep introspective work.

There’s a subtle, yet definite feeling of claustrophobia in this work. Sometimes it’s manifest in a physical sense, as in “Chrysalis,” and other times it’s expressed on a metaphysical plane, as in “The Great Destroyer,” in which time seems to have stopped. Is this a fair interpretation?

Yes. Your interpretations are thoughtful and honest and totally valid! I have heard similar responses to these particular images before, but I have also had some entirely unexpected interpretations. Several viewers described “Chrysalis” as an outdoor landscape with a large cliff and a low horizon, creating a feeling of openness. One viewer reached out to touch “The Great Destroyer” because they thought it was a 3-D piece (why they wanted to touch it, I do not know, but they were somehow compelled to reach for it and were confounded when it wasn’t a tangible thing to grasp). Other viewers thought that “The Great Destroyer” was a train coming straight at them, which created a kind of anxiety. These are great examples of how the viewer is the co-creator of the work, meaning that I create the images with certain intentions, but the viewer recreates them with their unique perspectives and feelings.  The Great Destroyer

The Great Destroyer

Some of the compositions seem to be arranged; others seem to be scenes you’ve documented without altering anything physically. But even in images like “Refuge,” which belongs to the latter category, there’s a feeling of instability, both physical and otherwise. The viewer is continually made to feel the precariousness of human existence, or perhaps the futility of ambition.

Actually, none of the images were arranged aside from my composition choices. They are all images that I made out in the world, using a 35mm camera, tripod and available light. Of course, I found some really unusual things that may feel arranged, but I look for that kind of serendipity. As far as these feelings of instability and the idea of the precariousness of human existence, these are perfectly valid readings of the images. I did compose many of these images to suggest a particular direction, but the viewer’s responses have been all over the map with “Refuge” and other similar images. I’m just excited to hear what my viewers come up with.

Is there an autobiographical resonance to this series?

Yes and no. I began this series long after a very difficult time in my life. The work was created as a reflection of my experiences with deep suffering. Nocturnal Sunrise is a collection of images that are inspired by my own experiences, but are not about them. I created this series during a state of redemption and healing, not in the grip of suffering. I believe that work made from an authentic, personal place can ultimately become universal in the right context. A Thousand Lonely Suicides

A Thousand Lonely Suicides

“A Thousand Lonely Suicides” is a pretty despairing image. Like Celine’s famous novel, it depicts a journey to the end of the night. For me, in fact, there’s a strong literary sensibility at work here, inclusive of Celine’s moral despair, J.G. Ballard’s use of visual metaphor, and the Gothic atmosphere of Poe.

There is definitely a literary sensibility in this work, but I am unfortunately not familiar with Celine or Ballard. Poe is an important influence for me, as far as his lush atmospheric descriptions and ability to illuminate the darkness with a tinge of romanticism. In particular, Poe’s short story “A Descent Into The Maelstrom” had a profound effect on me and I have tried to merge that subtle, yet frenetic energy into my visual language. William Blake’s poetry and etchings also move me deeply and have infused their influence into this series. In Blake’s poem “Auguries of Innocence,” there is the line “some are born to the endless night.” That idea always sends chills down my spine.

Do you feel the overall tone of this work is optimistic or pessimistic?

I like to think of the work as neither optimistic nor pessimistic, but paradoxical. The images may be read as light emerging from darkness, darkness overtaking light, light infiltrating darkness, etc., but ultimately all of these ideas can coexist together. It is my hope that paradox and ambiguity in the images will allow the viewer to determine whether they feel the work is optimistic or pessimistic or perhaps both. What Goes On

What Goes On

Do you perceive the world and/or people as fundamentally mysterious and unexplainable?

Ha-ha! Yes! Yes, I do! It’s the mystery and uncertainty that adds vitality and excitement to being a human being. Try as they may, scientists cannot compartmentalize the human condition into a nicely wrapped, rational package. The arts are the closest we can get to these whispers of truth, and even the arts ultimately fail to fully explain the vastness of what it means to be alive.

Many of these photographs are enigmatic to the point where meaning is something negotiated between the visual tableau and the viewer’s own emotional or spiritual baggage. I’m thinking in particular of “What Goes On” and “Severance.” Is this something you aim for?

Yes. Again, this ties in to my philosophy of the viewer as co-creator of the work. I strive for this sense of visual ambiguity in order to let the viewer’s conscious and subconscious mind find its own meaning. Severance

Severance

You evince a strong interest in geometric urban patterns — telephone wires, metal scaffolding, intersecting shadows, etc. While interesting on a purely visual level, they also seem to induce a sense of foreboding and entrapment.

For me, these graphic elements serve several different functions. First, they are designed to break up the picture plane with horizontal lines in order to create a sense of ordered chaos. Second, the crossed lines form archetypes that the mind may pick up on and respond to on a somewhat primordial level. For example, the archetypal symbol ‘X’ is loaded with paradoxical meaning, both obvious and subtle. Humans use the ‘X’ to denote when something is going to be removed, going to be put in, to mark something that is already there or used to be there, etc. There are thousand of interpretations within a single archetype, and I like to utilize them as recurring themes, both aesthetically and symbolically.

Is there something about the extra time and effort required to make photographs with traditional materials and processes that affects your approach?

Everything about this project took a lot of time and effort, including finding the right film, paper and developers; traveling to make the photographs; editing, printing, determining the correct presentation method, titling, and installation. I enjoyed all of these challenges as a process, not just as a means to a goal. I love the darkroom because it allows for a kind of mystical experience that you just can’t get sitting at a computer. I adore the arcane instruments illuminated by soft red light, the isolation from the outside world, and the joy of witnessing the genesis of an image from an ethereal source to a tangible object.  Gemini

Gemini

Have you been influenced or inspired by particular photographers? Or artists in other mediums?

I’m drawn to artists whose work emanates a kind of raw, guttural energy that pierces me to the core. Specifically, I love Stephen DeStaebler’s enigmatic sculptures; they are simultaneously unnerving and gorgeous, and unveil their mysteries over a period of time. I dig Sally Mann’s glass-plate photography series, “What Remains” because of its haunting atmospheric utterances and its overarching themes of impermanence and fragility. I’m heavily influenced by Anselm Kiefer and Antoni Tapies; two painters whose works are at once epic, graphically stunning and loaded with ambiguous metaphysical symbolism. Films like The City of Lost Children, Dead Man and Blue Velvet influenced my compositions and choices of lighting for this project. Music in general is a huge inspiration for my photographs, but musicians like Godspeed You Black Emperor, Nurse With Wound, Three Mile Pilot and The Black Heart Procession had an effect on the psychological undertones of Nocturnal Sunrise and also influenced some of the titles. I like the idea that art is interconnected and that photography isn’t all that different from music, painting and sculpture. Although I choose photography as my preferred means of expression, I have always been baffled by the separatist mentality that places one medium higher or lower than another. In my opinion all artistic mediums are paths to the same goal, whatever that may be. The Great Depression

The Great Depression

Are there any other themes or ideas you’re trying to evoke in this series?

I think that pretty much covers it. On a side note, it is difficult to gauge the scale and energy of this work in a magazine or a website. Something gets lost in the translation that can only be experienced by viewing the prints in person.

Is this an ongoing series, and do you have any other projects/series on the horizon?

I plan on continuing Nocturnal Sunrise as an ongoing series, but unfortunately have to find a replacement for the luminous textured paper that was discontinued by the manufacturer. I am working on a new series entitled Fierce Absurdity, wherein I am using the same high-contrast/full-tonal-range process as Nocturnal Sunrise, but focusing on more ridiculous subject matter. I’m hoping the synthesis of sinister tonalities and silly imagery will facilitate a paradoxical commentary on the absurdities of life.

[This interview appeared in Issue 77 of B&W magazine. Spend some time in the dark at: www.philipringler.com.]

Bob Witkowski: Rust Never Sleeps

“Straight” or “realistic” photography in some way or another usually points to the passage of time, either subtly or overtly. Not so with abstract photography, which generally has little connection to the real world. This is just fine with Bob Witkowski, who has a passion for shooting macro images of rusting junkyard automobiles that evoke both physical and metaphysical metamorphoses. A one-time law student and Yale graduate, Witkowski also studied at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, and began taking photographs in the early seventies. A chance opportunity to photograph an oil refinery led to a flourishing freelance career, during which he has worked for major news magazines, film studios, television networks, tourist boards, corporations and record labels. As fulfilling as this work continues to be, his real joy is making personal images where the only client he has to satisfy is himself. Bob Witkowski (Photo by Hannah Witkowski)

Bob Witkowski (Photo by Hannah Witkowski)

Where were you born?

I was born in January 1948 in New Britain, Connecticut.

Was there room for creative aspiration during your formative years?

New Britain in the 1950s was a prosperous industrial city with three distinct social classes: upper middle (professional, management); blue collar/lower middle (factory workers, union); and lower (the rest). My Dad was a factory worker. I was a bright and precocious kid, and because of that my family pushed relentlessly for school success and a career as a lawyer. Creative development? Dad was a prodigy musician, but left it all behind for the security of a factory job, marriage and a kid. I went to prep school on a scholarship and was lucky enough to attend Yale on a scholarship as well—all the time geared for a law career and being my family’s great white hope. I played piano, but I had no idea I would ever be a photographer or any sort of artist. Go figure. What I did know early on was that I never was comfortable living in the East. I would be depressed from November until Ash Wednesday, when I felt the hope that warm weather and the colors of spring were not far away.

Rust Macro 6, Missouri, 1974

Rust Macro 6, Missouri, 1974

How did you become interested in photography?

I was unhappy at Yale, although I did okay academically. It was 1966-1970, so I learned to drink and enjoy pot, acid, etc. I still did the shuffle to a law career, but I was completely disconnected. I got so many concussions playing rugby that I was 4-F, so Vietnam wasn’t looming on the horizon. I applied to law schools but don’t even remember or care if I got accepted. But what did happen in May of 1970 was the May Day Riots in New Haven. My suite mate was a stringer for Time magazine, and when the gassing came one night, he tossed me a Pentax Spotmatic, showed me how to load Tri-X and how to focus, set the camera at 125th at f5.6 and said, “Go shoot!” That was it for me. For the first time in my life I felt alive and connected. My head and my heart finally worked together, and my life made sense. The next day I called my poor Dad and told him that I knew what I wanted to do with my life, and it wasn’t law. Rust Macro 2, New Mexico, 2007

Rust Macro 2, New Mexico, 2007

Do you find any points of intersection between your commercial and fine art work?

When I arrived in DC after a year’s graduate work in photojournalism at the

University of Missouri, I found myself in the position of having to survive while trying to stay committed to my “art” at the time. My first break was to get access to the Gulf Oil Refinery in Philadelphia through the aegis of the American Petroleum Institute and its Director of PR, Robert Goralski, one-time correspondent for NBC News. I was paid nothing! I had little money at the time as well. I spent everything I had on several bricks of Kodachrome 25 and drove up to Philly and spent six days in paradise shooting 20 hours a day. It was at the refinery that I discovered I could be true to making images I loved while making industrial images that were sensuous, beautiful and a complete sellout. So I finally had something to drag around in a slide projector to show to industry trade groups and corporations around the DC, Baltimore and Richmond areas. It wasn’t an easy sell at first, and I paid my dues like anyone else for several years, but eventually it paid off for me professionally. I was fortunate to shoot in the golden days of corporate annual reports before Reaganomics altered everything. Early Rust Abstract

Early Rust Abstract

Aside from your “Roses” series, the “Rust” images are your most abstract work. Do you enjoy pushing further into non-representational imagery?

Yes. Actually, I took a long hiatus from shooting rust abstracts. For some reason I couldn’t “find” any great junk cars or I just was no longer able to “see” the patterns any longer. I don’t know what happened. But in the past three years, I began looking again…and I began seeing again. I believe it has to do with the depth of my grief over the death of my wife and the resulting realignment of my relationship with my two young children. I didn’t expect to be a single dad at age 62. Yet, something very powerful has happened to me, and some of it has been reflected in the resurgence in my work. It’s all equal, however, with my suddenly intense and close relationship with my daughters.

Was your decision to shoot these in color in part to provoke a warmer emotional tone?

Yes. When I came home from France earlier this year with a vast number of new abstracts of both rust and chipped paint, I actually converted some images into black and white just to see how they would look. Didn’t work at all. Not even when I used the Alien Exposure plug-in and toyed with infrared, Rodinal developer, Tri-X, etc. Grayscale just didn’t convey the emotions I experienced when I saw and made the original images.

Are these colors as you find them, or do you modify them any in Photoshop?

Since I’m slightly color blind on the low end of the spectrum, I’ve found that a little tweak for me in Photoshop is a good thing. When I feel comfortable with the final colors, I find that viewers like you respond very positively to them. Rust Macro, Arizona, 2003

Rust Macro, Arizona, 2003

Your colors are beautiful and sensual, never harsh. Is this a philosophic as well as aesthetic choice?

No matter how I “see” the original colors, I’m responding to them on some deep emotional level. It’s all relative. Throughout my professional career I was known for the almost Technicolor intensity of my color work. And that was way before Photoshop. I always bracketed like crazy, I shot under all sorts of lighting conditions, and I used 81A and Polarizer filters exclusively.

One characteristic of abstract imagery is the way it challenges people to reassess their visual environments.

I’ve never really thought like that, Dean. I have never thought in terms of having an “objective” when making abstract images…or more precisely, while searching for these little pieces of abstractions found in rust patterns. I crawl over junk autos on bright sunny days and cold overcast days, totally absorbed by the infinite intricacies I see in the viewfinder. The process of the shoot is a source of intense joy for me. And it’s quite simple, although if someone’s watching me I must be quite a sight. If I’m shooting analog, it’s just me and my Leica R4 with a motor drive, a Leitz 60mm macro with a Leitz extension tube fully racked out, and Provia Pro 100. The meter is usually set to aperture priority at f8.0. I don’t manually focus the lens; I move myself. I hold my breath while I shoot and then end up gasping for air in between takes. This goes on for hours and many rolls of film. The process is the same in digital, where I use a Nikon D-300 and D-300s and a Nikkor 105 macro with and without the extension tube. Not only do I experience the joy of seeing and making these images at the location and in the moment; I get to feel the same joy and intensity again when I scan the slides or work the RAW images on my computer. In what other art form do you get to experience that creative discovery moment over and over? Rose, Portland, Oregon, 2004

Rose, Portland, Oregon, 2004

Are you more interested in stirring the emotions or the intellect?

Either one. If my work elicits an emotional or an intellectual reaction, I’m honored. I don’t shoot with that in mind. My greatest mentor was my high school English teacher, Thomas Chaffee. He taught me many things that shaped me then and influence me to this day. First among them is this quote from D.H. Lawrence: “Never trust the teller; trust the tale.”

Would it be fair to say that your work is primarily concerned with the transformative effects of time?

Yes. But again, that’s a verbal concept that I would not have come up with.

Okay, so do you find beauty in decay?

I see beauty in evolution, in growth, in aging, in change, in transformation. There is the same beauty of transformation in my portrait of a street chef in Borneo. The drop of perspiration on his upper lip will transform to nothingness if we just wait a little bit. The petals in one of my flower still lifes will fall or wilt naturally through age if we just wait a little bit. Or maybe they won’t if they’re artificial. Who knows? In the end, does it matter? Rust Macro 1, New Mexico, 2007

Rust Macro 1, New Mexico, 2007

Although rust is a state of deterioration, the feeling I get from these images is one of organic growth or rebirth. Which state do you try to evoke?

Rebirth. And from that, hope.

One might almost take these photographs for life forms evocative of other planes or dimensions of existence. Do you get any feedback along these lines?

I do. There are several other Rust images that invite all kinds of interesting, wild and imaginative—comments. I love that. Again, these images provoke mostly emotional responses that range from whimsical to serious to the vintage yet valid “Oh, wow!” syndrome.

Is this an ongoing series?

Yes…as long as there’s rust, junk cars, peeling paint, rotting textures, and surly yet lovable junkyard owners who aren’t threatened at what I’m doing when I show them samples of my work and ask permission to shoot on their property, I’ll do it as long as I can hold a camera. The process and the results are a source of continuing joy and fulfillment for me. Rust Macro 4, Missouri, 1974

Rust Macro 4, Missouri, 1974

Your work is wonderfully varied—you can’t be pinned down to a particular genre or approach. How do you see your photography developing in the future?

This is the highest compliment I’ve received about the breadth of my work. This comment is one of the first that shows someone gets what I do and what I see. For my entire career clients have seen me only as a corporate shooter; gallery owners, museum photo directors have seen this “varied” style as a weakness rather than a strength. The feedback I’ve always received from the art side has mostly been one of frustration because I haven’t been able to be “pinned down to a particular genre or approach.” It used to hurt and frustrate me.

Now it no longer matters. No matter the image I see and create, whether it’s a color rust abstract, a stunning black-and-white portrait, a portfolio of boxers in gyms in Watts, street photography, architecture, whatever I shoot….it’s all processed by the same brain, seen by the same eye, felt by the same heart, embraced by the same soul. At age 62 I feel like I’m more alive and more attuned to my world visually and emotionally than I ever have been. I feel that I’m at a newer and different stage in my life. I can be awed and excited and moved by the images of the life around me in a much different way today than I was 10, 20 years ago. I never expected this to happen quite this way. Actually, I never expected any of this to happen. So, yes, my photography is evolving and growing in ways I could never have imagined. Most of my friends are retired. I’m just hitting my stride…I never planned any of this. I’m having a ball and I’m very grateful. Street Chef, Borneo, 1990

Street Chef, Borneo, 1990

(I profiled Witkowski for the July 2010 issue of COLOR magazine. You can check out more of his intriguing color imagery here: http://atwitsend.org.)